New Zealand food manufacturers have been named and shamed in a controversial new study that says some companies are not doing enough to reduce the largest cause of ill health in this country…unhealthy diets. Is the industry really taking this seriously? Kathryn Calvert reports.

When young 5th year University of Auckland medical student Apurva Kasture decided to look at the nutrition commitment of 15 local packaged food manufacturers, two beverage manufacturers, two supermarkets and six quick-service restaurants in New Zealand, she didn’t quite expect what she found.

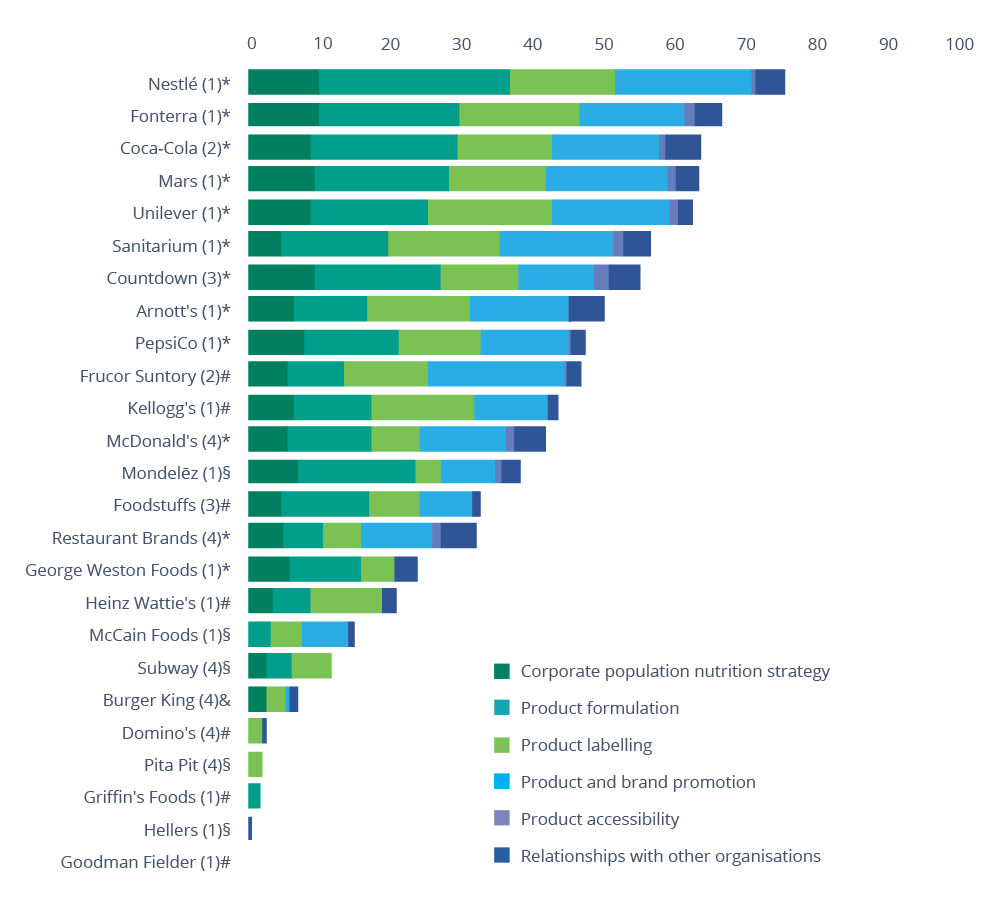

Assessing company policies across six key domains – obesity prevention and nutrition, corporate nutrition strategy, formulation, labelling, promotion, accessibility and relationships with other organisations up until the end of last year – she found a disturbing variability in effort. Although encouraged by the engagement of many companies and the steps they were making towards more positive outcomes, Kasture was also dismayed at the reticence of other companies that needed to ‘pull their finger out’.

“Some companies have taken positive steps in response to pressure from society to improve their products with Nestlé, Fonterra, Coca-Cola, Mars and Unilever the top performers,” Kasture says. “But companies could play a much greater role. There was a large variation in the scores from 0 to 75 out of 100, with eight companies scoring less than 20.”

Some NZ food companies, Kasture says, are performing well and are meeting good practice benchmarks. In all sectors, companies are incorporating population nutrition and/or obesity prevention in their overarching corporate strategy to some extent, and there is a push to reformulate products to reduce levels of sodium. Companies are trying to reduce sugar in specific food categories, and are committed to the Health Star Ratings on food products. Most understand the Advertising Standards Authority’s children and young people’s advertising code, but that’s where the good news ends.

“There is considerable room for improvement for most companies,” Kasture says. “The conversion of commitments into practice needs further evaluation. Stronger action is needed across all four sectors to improve food environments and population nutrition.”

Mention the study to Katherine Rich, and you get a slightly different perspective. The head of the NZ Food and Grocery Council says manufacturers come out of the survey relatively well, “given the slanted criteria. Food manufacturers are very conscious of the issues around obesity and its causes, and are continuing to do a huge amount of work around reformulation to remove salt, fat and sugar,” she says. “There are now more low-cal and no-cal product options available to consumers than ever before. The seriousness with which manufacturers take the issue is evidenced by the more than 3600 products on supermarket shelves that carry Health Star labelling.”

Many companies have nutritionists who advise on product ingredients, Rich says. “Including in the study that some companies declined to participate was misleading. It was like pronouncing someone last in a race they didn’t enter. Researchers should never assume that, because they haven’t been able to secure information, that it doesn’t exist. Ranking companies that didn’t take part showed that part of the research was to ‘name and shame’, and that seldom achieves anything apart from publicity.”

Professor Boyd Swinburn, well-known health advocate and Kasture’s study supervisor, is more skeptical. “Many food and beverage manufacturers and supermarkets are reformulating products to reduce levels of sodium and have targets to reduce sugar, but this is highly variable and rarely measurable,” he says. “Nestlé has a target for lowering sodium, sugar and saturated content. Frucor Suntory commits to have one-in-three products sold to be low or no sugar by 2030. (However), more companies could develop targets to reduce sodium, sugar, saturated fat, trans fat and portion sizes. Companies really could go beyond the existing weak Code and include children up to the age of 18 years in marketing policies, and stop using promotions like cartoon characters and interactive games for marketing unhealthy food products to children.”

Countdown and FoodStuffs have committed to implement the Health Star Ratings across all their own-brand products, Swinburn says. Unilever uses a publicly available nutrient-profiling system to determine the type of nutrition or health claims that are acceptable for products to carry. Although quick service restaurants provided nutrition information online, few provided calorie labelling on meals on-site. Companies performed relatively well on product labelling, with many committing to implement the Health Star Ratings and providing nutrition information on their foods and meals online, Swinburn says.

“Companies had few commitments to restrict accessibility of less healthy foods and improve accessibility of healthy foods. Recommended actions are to limit price promotions on less healthy products, make all checkouts free of junk food and for quick-service restaurants to not provide free refills for soft drinks.” A positive step would be to see population nutrition become a priority focus within the corporate strategy. Swinburn says Nestle and Fonterra are leading the way by recognising national and international nutrition policies.

Fonterra’s head of nutrition Mandy Wigzell is proud of the company’s commitments, and its strong performance in corporate nutrition strategy. “As a global dairy nutrition company, we’re committed to sharing the goodness of dairy and are always looking for ways to continually improve the nutritional value of our products,” she says. “Our new global nutrition guidelines, which have been independently reviewed and endorsed by the NZ Nutrition Foundation, drive that improvement.”

It’s the same at Sanitarium Health & Wellbeing. A statement from the company says the report will encourage the country’s major food companies to do more to address rates of overweight and obese people in the New Zealand population. “Our commitment to helping New Zealanders enjoy a happier, healthier life is at the core of our company purpose, it’s why we exist. We believe good nutrition is integral to this; we also acknowledge it’s only one part of the solution. We are considering the recommendations proposed by the University of Auckland as well as the overall assessment framework. This will help us refine and prioritise our actions in contributing to better population health outcomes into the future.”

Some companies were transparent about relationships with other organisations by publishing funding for external research and publicly committing to not make political donations, with Coca-Cola, Arnott’s and Restaurant Brands the top performers. The study also noted as good practice Fonterra’s engagement with the KickStart Breakfast Programme, which provides nutritious breakfasts to children in more than 800 schools around the country; and the Fonterra Milk for Schools initiative, which provides free milk to participating primary schools. “These are all part of our commitment towards the health and wellbeing of New Zealanders,” Wigzell says.

The report was funded by the Health Research Council and was based on publicly available information (up to the end of 2017) with half the companies providing additional information. It was assessed using the BIA-Obesity tool (Business Impact Assessment – Obesity and population nutrition) developed by INFORMAS, a global network of public health researchers that monitors food environments worldwide, co-ordinated by the University of Auckland.

The study measured commitments and transparency but did not assess the actual performance of companies in meeting those commitments or the overall healthiness of their product profiles. These will be the focus of future research. Tackling the unhealthy food environment requires a comprehensive response from government, the food industry, the health sector, and the community, Swinburn says.